One of the nice thing about school being out and traveling a bit is it gives me more time to read books for fun. My favorite genre is probably the travelogue. Mark Twain, P.J. O’Rourke, Paul Theroux? I love them all. And I’ll even define travelogue broadly to include historical fiction, like my favorite books by Louis de Bernières. Even New Jack by Ted Conover is a travelogue of sorts, since it took me to Sing Sing, a place I’ve never been. Hmmm, I guess by this logic Cop in the Hoodcould be called a travelogue. But I don’t think it is. But I do like my book.

In the past month, along David Sedaris’s When You Are Engulfed In Flames, I’ve been able to read Gerald Brennan’s South From Granada, which is a very good anthropological-like account of 1920s life in a Spanish village. But perhaps you might only care about life in Yegan if you happen to be hiking through the Spanish Alpujarras.

Chris Stewart writes about the same region in present times in a much more light-hearted and readable way. I read the third of his trilogy, The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society. Good stuff. And I’ve told myself, somewhat unconvincingly, that I’ll buy and read the first two.

In a different genre, I was not Swayed by Sway. It does not succeed at being the Malcolm Gladwell book it wants to be. Some of Swaywas interesting, but I don’t need a rehash of one dumb psych experiment after another to tell me that economic rational-choice theory doesn’t have all life’s answers. I wanted more discussion and relevance to the real-world.

So maybe I should stick with travelogues. For some reason I think the British are the best at this genre. Maybe it’s the old colonialist in them. Maybe they’re don’t mind being culturally chauvinistic. They’re certainly less concerned with style killing political correctness. Perhaps these attitudes are no way to rule an empire, but it makes for good reading.

Most travelogues either start happy and end happy (“what a wonderful trip with great people and food!”), start unhappy and end unhappy (“oh, my woeful journey into the heart of darkness… and I would kill for a good cup of tea!”), or start unhappy and end happy (“I just couldn’t be happy until I learned to let go of my neurotic hang-ups and be at one with these wonderful if somewhat simple people!”).

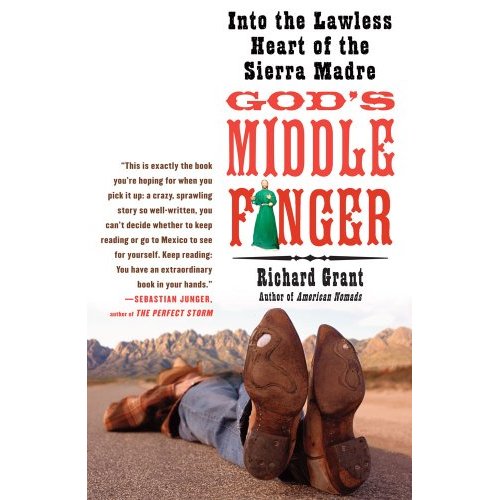

It’s the rare travelogue that starts happy and ends unhappy. And this brings me to the best book I’ve read since Maximum City: Richard Grant’s God’s Middle Finger: Into the Lawless Heart of the Sierra Madre.

Talk about unhappy! This book ends–and I don’t think I’m spoiling anything because the book starts with a sort of flash forward so you know where it’s going, but skip the next paragraph if you don’t want to read the last line in the book:

I never wanted to set foot in the Sierra Madre again. The mean drunken hillbillies who lived up there could all feud themselves into extinction and burn in hell. I was out of courage, out of patience, out of compassion. They were sons of their whoring mothers, who had been fornicating with dogs.

The first line of the book is, “So this is what it feels like to be hunted.” Why does this man, Richard Grant, travel into the lawless, wild, and narco-controlled Mexican Sierra Madre mountains? Well, for some of the same reasons that many sociologists enjoy research and some of the reasons I enjoyed policing:

We drank four or five gourds each and got nicely buzzed there on the rim of Sinforosa Canyon and it occurred to me that this was more or less the moment I had been looking for when I set out on this journey. Here I was in the heart of the Sierra Madre, about as far from consumer capitalism and the comfortably familiar as I could get, drinking tesguinowith a wizened old Tarahumara and feeling that edgy, excited pleasure in being alive that follows a bad scare. It was an uncomfortable realization. To put it another way, here I was getting my kicks and curing my ennui in a place full of poverty and suffering, environmental and cultural destruction, widows and orphans from a slow-motion massacre. I tried to persuade myself that I was going to write something that would make a difference and help these people, but my capacity for self-delusion refused to stretch in that direction.

God’s Middle Fingerneeds no rationalization to read, but I could justify my time reading because I wanted to learn about drug production in Mexico. It’s not a pretty picture. And it closely resembles the destructive prohibition-caused drug culture I saw as a cop in Baltimore’s Eastern District.

Why did drug cultivation increase the murder rate? “Because drugs give people money to buy gun, alcohol, and cocaine,” said Isidro.

He didn’t think that statement required any elaboration but I asked him to elaborate anyway. “People get more aggressive and paranoid. They kill more easily and then the dead man’s family has to avenge the killings.

I was reading a fascinating book with a similar thesis. Its title translates asThe Sierra Tarahumara, A Wounded Land, The Culture of Violence in the Drug-Producing Zones. Its author, a professor in Jaurez called Carlos Mario Alvarado Licon, based his ideas on prison interviews conducted with convicted murderers from the Sierra. He found that they were nearly all model prisoners, with no prior criminal record, and no remorse or regret for what they had done. … They told of their crimes “serenely” and were convinced they had done the right thing.

In the Sierra homicide is no dishonor. Killing is a part of life, a circumstantial action, generally vengeance for another killing. However, on occasion it is a symbol of pride, when vengeance was done and the law taken into one’s own hands…. Homicide is a form of maintaining the social order where the official authority is absent, unjust or corrupt, and particularly where it fails to punish aggression or offense to the family.

…

When Isidro’s father was killed, his mother implored him to take vengeance. “It was very hard, but I decided not to because if I avenged my father, I would end up losing my brothers and maybe my uncles. It wouldn’t bring back my father and would bring more sorrow into my family. My mother didn’t understand. She never really forgave me.”

Don’t go thinking that drug decriminalization in Mexico for personal possession is going solve this. The problem isn’t possession. It’s wholesale prohibition of drug production, distribution, and sales.