This is Part Two. Part One is here.

Jill Lepore has an article in the New Yorker about the invention of police that somehow manages to sidestep every thing I know about the history of police. I know a little about the history police history. Much more, I suspect, than Jill Lepore.

I discussed a key problem of Lepore’s perspective in my last post. She writes through a lens, a worldview, in which she believes that two-thirds of people aged 15-34 who go to the Emergency Room are there because they were beaten by police or security.

It’s crazy talk. And it makes me question everything else she writes on the subject.

Her article has so many errors. But rather than refute her point by point (though there’s some of that), I’m just going to present my own history of the invention of police. Now this is just one version of police history (albeit a pretty mainstream one). I’ve got no grand narrative here. It’s what I consider “objective.” That used to be goal. Now? I don’t know. If you want to put your spin on this to apply it to current events, feel free. But that’s on you. And yes, of course this is over-simplified. But here’s my brief history of the invention of police in America, from 2050BC to 1870AD, from a New York City perspective.

- Long before there were police, society and governments and communities maintained order. That’s important to keep in mind.

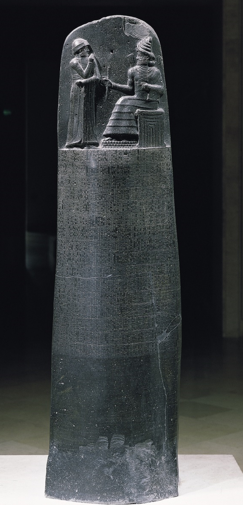

- 1800 BC, 3,800 years ago, Hammurabi invents the “rule of law.” Or at least he was smart enough to carve it in stone, so we give him credit whether he deserves it or not.

- The Old Testament (Exodus 21:24) talks about an “eye for an eye, tooth for tooth.” Harsh? Maybe. But much softer than Hammurabi! Justice in the Judaeo-Christian world changes when Jesus says, “go and sin so more” (John 8:11). Retribution vs restorative justice? Deep.

- Not too much innovation in the west from then until the Anglo-Saxon “kings peace” concept that all crimes are crimes against the king, and the state will keep a monopoly and prosecution and punishment, thank you very much.

- James Watt’s steam engine comes along in 1780 and you got your Industrial Revolution. And with it, urbanization, disorder, gin, and the growth of crime and disorder in London. America was a few decades behind.

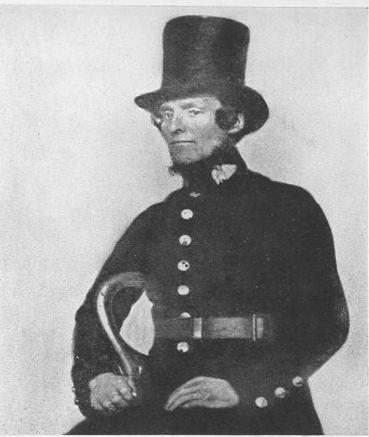

- Very long story very short: Sir Robert Peel invents and implements the concept of modern police in 1829 London, the Bobbie. It’s to maintain order and prevent crime, he says. It’s so not an army we’ll put them in blue instead of red.

- The word “police” isn’t new. What has changed is the concept of “policing.” There had been watchmen since forever, and America certainly had bounty hunters and slave catchers long before 1829. Britain had frankenpledge and tithing. Before that the Romans had the “urban cohort,” Vigeles, public servants who did some of the things associated with police today.

But we define “police” as full-time public employees, most in uniform (originally blue, with hat, rattle, and baton) whose purpose is to prevent crime and disorder, and who also have the power and obligation to arrest criminal offenders.

What Peel did was combine a lot of public functions into one, and center it around the idea that police should be public servants whose primary (almost exclusive) purpose was to “maintain order and prevent crime.” He was pretty clear about this (though note he never wrote his famous “principles“). I’ll also give Peel credit for inventing foot patrol. That’s kind of big deal in the policing context. Public patrol is very different from “guard this property.” I’d say it defines policing. - Peel’s policing idea was adopted in New York City in 1845. It quickly spreads from New York to other American cities. But I’m going to focus on New York.

- Unlike police in London, American police (at first) don’t wear uniforms, but more important, police in New York are under local (ward aldermanic) political control. They also carry guns.

- In the South, police remains a slave catching / bounty hunting proposition until Reconstruction. During Reconstruction, Southern cities had a pretty clear divide between antebellum slave catchers and the post war “modern” policing imposed by northern occupation. But Reconstruction ended up being too brief, police in the south reverted to their racist role as enforcers of slavery-based Jim Crow.

I try to cover that in my first class in an hour. It’s not easy. In my second class I turn to Kelling and Moore’s Three Eras and Williams and Murphy’s Minority View. I add some August Vollmer (and shame on Lepore for making him sound like some cracker), Civil Rights, the LA Riots, and the NYC crime drop, and pretty soon you’ve got a decent foundation for me to get on with whatever the class is supposed to about.

In the New Yorker, Lepore says:

It is often said that Britain created the police, and the United States copied it. One could argue that the reverse is true.

You could argue that, but you’d be wrong. And Lepore is not very convincing, at least to anybody with any knowledge of police history.

Lepore stresses Patrick Colquhoun. But not because of his contributions his dockside “River Police” (usually the “Bow Street Runners” get more credit, but both were, still, in essence, bounty-hunting operations), and less for his 1800 treatise on police that talked about the “new science” is which police should “prevent and detect crime” (this no doubt this influenced Robert Peel), but because [gasp] Colquhoun had spent years in Colonial Virginia and owned shares in a sugar plantation in Jamaica. Ergo, through Colqohoun, American police are rooted in slavery. Though Lepore admits that not much came of Colquhoun’s idea for another generation, until the London police started by Robert Peel, to whom she gives two sentences.

Why does that matter? Because one could either see the invention of police as good, as a noble concept, as a way in which society tried to defend the community and protect those most vulnerable. I actually believe that. But even if I didn’t, I don’t see why I wouldn’t want to believe it. Or you see American police as rooted in slavery and doing little more than serving White Supremacy. I certainly know the dark side of police history as well as anybody. It’s real. But that’s not and never has been the ideal. It’s not what American policing is rooted in. American policing doesn’t come from slavery. And it’s certainly not why American police expanded.

Lepore says:

It is also often said that modern American urban policing began in 1838, when the Massachusetts legislature authorized the hiring of police officers in Boston.

Actually, no. Nobody outside Boston ever say that.

For what it’s worth, in Baltimore you’ll sometimes hear Baltimoreans say they had the first police (established 1784). And a Glaswegian might tell you modern policing started with the Glasgow Police Act of 1800 (which has more merit). This is like rah-rah boosterism. Not real history.

I mean, even in Boston the Boston Police department doesn’t claim American urban policing began in 1838 Boston. The Boston police were established in 1854, a date Lepore somewhat sloppily references later in her article.

To be generous, if this isn’t your field, one basic source of confusion is that the word “police” is an old word. And sometimes people were paid to “police.” What changed is the meaning of the word. To be a a police officer didn’t mean what we think it means until Peel’s Bobbies hit the street of London in late 1829. Peel’s model is the one that worked, the one that lasted, and the model that was copied in America (and is given credit in every policing textbook).

From 1829 London, the idea of “preventative police” spread. (And the successful implementation of policing in London is great story, well worth reading about. It was not an easy lift.) In 1838 the New York Morning Herald wrote: “The new police system of England is to be introduced into South Australia, and two London officers have been sent out.”

From the New-York Daily Tribune in 1842:

Our citizens are all agreed that a thorough, radical Reform is needed.

Such are the general features of the Plan proposed. It seems eminently simple and well calculated to effect the great object for which any Police is needed – the prevention of crime.

Because we already had detectives and people running around to catch thieves for profit. Here’s a letter to the editor of the Daily Tribune:

I fully agree with you that a Police is wanted to take the place of the present Watchmen, Constables, &c. I saw, during some years’ residence in London, the effect of the new Police established by Sir Robert Peel; and I think one of that plan for this city would not be far from the best. The necessity of keeping them on duty at all hours is unquestionable.

And this is not too long after the War on 1812. Revolutionary War veterans were still alive. It wasn’t like “it’s British” was a great selling point. But there was no mistaking what the “new police plan” was modeled on. This isn’t controversial.

The first (abortive) New York police superintendent was mocked, according to the New York Herald, because he gave he copied a long speech, “word for word from a manual of instructions to the Liverpool police, published some half dozen year ago.”

There’s no reference to slavery. Nothing about Boston. But a whole lot about preservation of the peace and good order, which is straight from England. New Yorkers weren’t looking back to slavery, they were looking across the Pond to Peel.

From David R. Johnson’s (1981) American Law Enforcement: A History:

The reform of the London police attracted favorable attention in America shortly after the bobbies began patrolling their beats.

…

In an era when an attempt to collect accurate crime statistics had not even been made, it is extremely difficult to determine whether crime was actually increasing. We can say, however, that concern over property offenses had become widespread. Citizens arming themselves to defend their homes and persons was only one indication of this growing fear. Such measures had been unthinkable prior to the 1830s. Fear about this kind of crime, combined with dismay over the decay of social order, therefore made a powerful argument for police reform.

…

New York was the first American city to adopt a lasting version of a preventive police.

American policing — preventive police, a “new police” — started with the New-York Police Bill, written in 1844, but not passed until 1845. Objections came from Nativists (anti-immigrant) opposition to what they saw (correctly) saw as an immigrant dominated police force. This speech was given outside City Hall:

They … are now about to pass an odious and base police bill to bind us down. (Cries of shame, shame.) They will then appoint persons to office, and those men will not be native born citizens. (Cries of shame).

We have had to encounter much opposition from these foreigners. In the ward were I reside the Greeks and the Hessians deposited their ballots, and when I asked them were they resided, the inspector said he would challenge every one at our side. It was not enough for them to have the privilege of voting: no, for when they found they were cut down at the polls, they then had their Greeks and their Dutchmen to kick up a row. and when we claimed to have the men arrested we were then struck down (cries of shame).

I saw a state convict let loose from Blackwell’s Island by the Governor, to pollute our polls by his presence. I saw him parading in our streets at the head of bands of blood-thirsty ruffians, banded for the purpose of preventing the native citizens from giving their votes. Old Tammany Hall must die. (Cheers). It is already tumbling, and for ever let it be damned and lost, and the Native American party rise and extend its influence. [Mr. Whitney concluded by exhorting his party to rally round the glorious banner, and] conquer the Greeks and Germans, and all other foes of reform. (Great applause).

But the the New York Police Bill passed the next year and took effect in June, 1845. George Matsell was appointed commissioner on June 17, 1845 and would serve for 13 years (plus 2 years for a second term later on). The main points:

Article 1

§1 The watch department, as at present organized, is hereby abolished, together with the offices of marshals, street inspectors, health wardens, tire wardens, dock masters, lamp lights, bell ringers, day police officers, Sunday officers, inspector of pawn brokers and junk shots, and of the officers to attend the poll at the several election districts of the city and county of New York.

…

§2 In lieu of the watch department and the various officers mentioned in the foregoing section, there shall be established a day and night police of not to exceed seven hundred and fifty men, including captains, assistant captains and policemen.

…

§5 Each ward of the city of New York shall be a patrol district.

…

§12 It shall be the duty of the policemen to render every assistance and facility to ministers and officers of justice, and to report to the captain all suspicious persons, all bawdy houses, receiving shops, pawnbrokers’ shops, junkshops, second hand dealers, gaming-houses, and all places were idlers, tipplers, gamblers, and other disorderly and suspicious persons may congregate; to caution strangers and others against going into such places, and against pickpockets, watch-stuffers, droppers, mock-auctioneers, burners, and all other vicious persons; to direct strangers and others the nearest and safest way to their places of destination, and, when necessary, to cause them be be accompanied to their destination by one of the police.

…

Article IV

Compensation of officers

§2 No fees or compensation shall be charged or received by any officer for the arrest of any prisoner… [or] the issuing of any warrant, subpoena, or other process. Any magistrate or officer violating the provision of this section shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be subject to the pains and penalties for such an offence.

§10 No member of the police department shall receive any present or reward for services rendered or to be rendered.

The new police were called the “new police” because they were, in fact, not just an evolution of the old. The old system was abolished and at least 12 municipal functions were absorbed into one “new police.”

But anti-immigrant sentiment was strong. The pro-new-police and not particularly Nativist Herald wrote in June 1845:

The Organization of the New Police is proceeding rapidly under the new Superintendent, Major Matsell. About five hundred men have passed the ordeal, and some two or three hundred incompetent candidates been rejected. … The nominations are made by the Aldermen of the Wards, and in some instances they have been so silly as to nominate men who could neither read nor write; some of these candidates being Irishmen, who have all, of course, been rejected, although nothing like “native” feeling exists in the selection. Adopted citizens, if competent, are just as eligible as any others.

But, unlike the Bobbies, these “new police” weren’t in uniform. This was a big issue for a while. The New York Herald emphasized the goal of “public safety” and made a plea for uniforms in early July:

We sincerely wish they had been more proscriptive in this particular, and made a uniform as essential feature in the police organization…. Let us have a uniform–we are no admirers of hogs in armor, but by all means let our police dress as policemen.

[Could this be the first ever reference to cops as pigs?]

There was a great fire in New York in July, 1845. Three hundred buildings burned and lives were lost. Troops were sent to prevent looting. The ever supportive Herald noted:

The police along Broad, Pearl, Stone, and William streets, was most energetic, at the same time civil and firm. The Value of the new body was spoken of by all in the highest terms, and have doubtless been the means of preventing the plundering of some thousands of dollars worth of property.

Two days later, still discussing the terrible fire, it was noteworthy enough to mention:

The Police wore large metal stars on their coats on which are the city arms, and the word, “Police.”

And the “new police” were often referred to as the “star police.” Both expressions seem to have died out by about 1850.

The New York new police lost the support of the Herald in late 1847, which noted that crime was up, and around 20% of the force had resigned or been fired. This was probably true, but paper’s objection may have been politics and the election of Mayor Brady (anti-Tammany). Or maybe there was a new editor at the Herald? But just a year earlier the paper was lauding the New Police for their “judicious use of authority” and usefulness in “the prevention of crime.” In May 1847 Mayor Andre Mickle (Tammany) went so far as to advocate for the complete abolition of the police system and a return to a system of night watchmen:

It has been in operation a sufficient time to enable us to form a just estimate of its worth, and I regret the necessity which compels me thus officially to state, that so far as my own observation extends, it has failed to meet the just expectations of the community.

It’s hard to follow all the local politics. But they matter. The Herald also highlighted the problem of corruption in policemen serving at the will of local ward aldermen:

Let a policeman make a descent on one of the lottery or policy shops in Broadway, and the changes are against his holding officer another year. The owner of the such shop possesses political influence, which he will exert against that policeman. And he will be backed by all his associates in the same business, in running and hunting down the faithful officer who has dared to fulfill his duty by enforcing the law

The paper seems to become pro-police again three months later, with the swearing in of Mayor Havermeyer. I could go on. But, to paraphrase Tip O’Neill, all policing is local. In a few very short years, other cities copied the New York “new police” model. And with the notably exception of the enforcement of the extremely unpopular (in the North) federal Fugitive Slave Law, the era of for-profit bounty hunting and policing for profit (at least legal profit) ended.

The New York model spread across America. Johnson:

Police reformers in other cities did not adopt every feature of New York’s plan. But there were enough similarities to say that New York served as a kind of model for the campaigns to establish preventive policing elsewhere. New Orleans and Cincinnati adopted plans for a new police in 1852. Boston and Philadelphia did so in 1854, Chicago in 1855, and Baltimore in 1857. by the 1860s, preventive policing had been accepted in principle, properly modified to meet American conditions, in every large city and in several smaller ones. This was an important achievement.

Let me just quickly get up to the start of today’s NYPD before ending. The NYPD actually does not descend from the “new police” of 1845! There were the Astor Place Riots of 1849. And in 1853 power to hire policemen was taken from local ward aldermen and given the mayor (Mayor Westervelt). This was progress, probably. Also in the early 1850s the size of the New York Municipal Police Department increased, cops were finally forced to put on a uniform, and police received military-like drill training (including baton training). And technology is always improving! The “magnetic telegraph” connected all the various stations. The telegraph actually precedes the police whistle, which won’t be invited until 1884. Want backup to deal with ruffians? Bang your night stick on the ground or fire off a few rounds into the air. “Service pistols” didn’t because standardized until Teddy Roosevelt required them as police commissioner sometime around 1895 (before that cops carried whatever gun they wanted to).

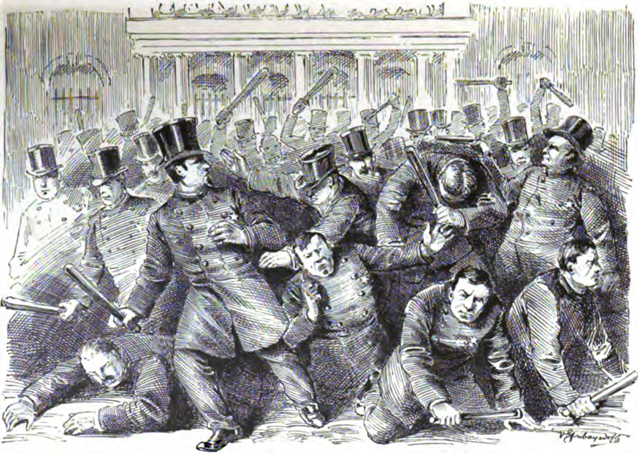

All this leads to New York State’s abolition of the Municipal Police in 1857. Corruption this; brutality that; nepotism this. But it was about power and politics and anti-immigrant sentiment. The state abolished the Municipals. The state established (and controlled) the new New York City Metropolitan Police. For a while there were two police departments as the Municipals sued in court against the legal power play. They wouldn’t turn over their property (and lose their jobs) to the upstart police. When the New York Appeals court ruled the legal shenanigans constitutional, the Metropolitans had the law on their side. It was all over but the shouting. Except…

The Municipals didn’t go down with a fight, literally. On the steps of City Hall! I can’t believe there’s no book dedicated to this: a City Hall battle between two New York City police departments. Mayor Wood barricaded himself in his office. The siege ended only when Wood faced the possibility of an artillery bombardment! Just so happens an army regiment was passing by, so the Metropolitans borrowed a piece or artillery and turned toward City Hall. And so begins the NYPD, established 1857. Everything changed and nothing changed. The state returned control of the police department to the city in 1870.

I’m waiting for Part 3. The lesson so far seems to be that the politics of policing haven’t changed in about 150 years.

Excellent work…I did not read her original article, but I so appreciate your slow and deliberate precision in your remarks. I can’t believe how irresponsible she is. Well, actually, I can…

What about Paris? I understand they had an early police force that was also influential in other big cities.

You should submit this to the New Yorker as a rebuttal piece. This nonsense and similar I’ll need to be taken head on.