The NYPD released its response to the “quality-of-life policing is bad” report issued by the NYC Dept of Investigation. Guess what? Quality-of-life policing is good! (The original report, the one this responds to, is titled, and I’m not joking: “The New York City Department Of Investigation’s Office Of The Inspector General For The New York City Police Department Releases A Report And Analyses On The NYPD’s Quality-Of-Life Enforcement.”)

Here’s what I wrote about the DOI’s report. I was bit gentle. Well Bratton and his people sure as hell are not. From Azi Paybarah in Politico describes it like this:

Bratton, who is scheduled to step down Sept. 15, said the June 22 report from the Department of Investigation’s Inspector General for the NYPD is of “no value at all” and that the office does not have experts on staff capable of analyzing NYPD work.

The report has an “incomplete understanding of how quality-of-life policing works and mischaracterizes Broken Windows as zero-tolerance, which it is not, and never has been,” Bratton said during an hour-long press conference at police headquarters. “Police go where people call. The vast majority of quality-of-life calls come from some of the poorer neighborhoods in our city.”

Bratton also cast doubt on the ability of the OIG-NYPD to analyze police work.

“I’m not sure of the quality of the researchers at the OIG,” he said. “I think we made it quite clear that if you want to delve into these types of areas, you’re going to need experts, not amateurs. Otherwise, you’re going to get the rebuttal that you’re seeing here this morning where we have a lot of experts within the NYPD [and] access to experts who are objective reviewers of the issue [that] the IG just, apparently, does not have, based on the poor quality of this report.

Here’s the first footnote from the NYPD’s report, which actually is a very good point:

The OIG report contains numerous modifiers and disclaimers that seem to contradict its own conclusions in many places. On the one hand, it strives to support the conclusion that there is no positive correlation between what it defines as quality-of-life enforcement and decreasing felony crime, but, on the other hand, it acknowledges that this conclusion cannot be reasonably drawn. It is as if the report’s authors wish to insulate themselves from possible criticisms by preemptively mentioning these criticisms in their report without allowing any of the criticisms to alter their conclusions. Taken together the disclaiming statements in the report form a virtual rebuttal to the report itself.

See, the report said it wasn’t a critque of Broken Windows, but we all knew it was. And that is exactly how the media summerizedthe report.

The NYPD response is a thorough report. I’ll highlight parts that illustrate Broken Windows. (I’m assuming you’re not going to read the whole report).

From page 10:

The Broken Windows Theory does not assert that 20 more misdemeanor arrests, for instance, will result in one or two fewer felony crimes. Rather, the concept holds that a general atmosphere of order and a general sense of police presence resulting from the enforcement of lesser crimes, will reduce the opportunity for more serious crime with generally positive results.

Page 11:

Misdemeanor arrests and summonses should not be used as simple surrogates for quality-of-life policing which has many other dimensions. Police officers can effectively respond to reports or concerns regarding quality-of-life conditions without arrests or summonses simply by dispersing groups, warning people to cease disorderly activity, establishing standards of behavior, and assisting with social service interventions.

Page 12:

Enforcing quality-of-life standards, without actually using misdemeanor arrests and summonses, still relies on the ability to invoke these sanctions. Telling people to move along when they know an officer can arrest or summons them is far more effective than it would be if they believe the officer cannot. Police officers require the fundamental authority to manage street situations and the option to move swiftly to criminal sanctions when necessary.

Page 15:

There actually is a strong statistical link between minor and felony criminals. The populations that commit both types of crime overlap to a significant degree. About half of all misdemeanor arrestees in New York City in recent years have had prior felony arrests, and nearly three quarters of felony arrestees have had prior misdemeanor arrests. [Ed note: This is surprisingly low. I would have guessed something closer to 90 percent.]

Page 16:

From the Broken Windows perspective, street management is a critical element in controlling street violence. It is an observable phenomenon that drunken, carousing groups may become involved in violence as an evening wears on. Summary enforcement, or police intervention prior to the violence, is one way of controlling it.

Page 18:

Quality-of-life enforcement should not be confused with reasonable-suspicion stops. Reasonable-suspicion stops are based on a significantly lower standard of reasonable suspicion, whereas misdemeanor arrests and summons issuance each require probable cause, the same standard required for felony arrests. The NYPD uses quality-of-life policing as a way of countering more serious crimes, but it does not make misdemeanor arrests and issue summonses without meeting the probable cause standard.

Page 19:

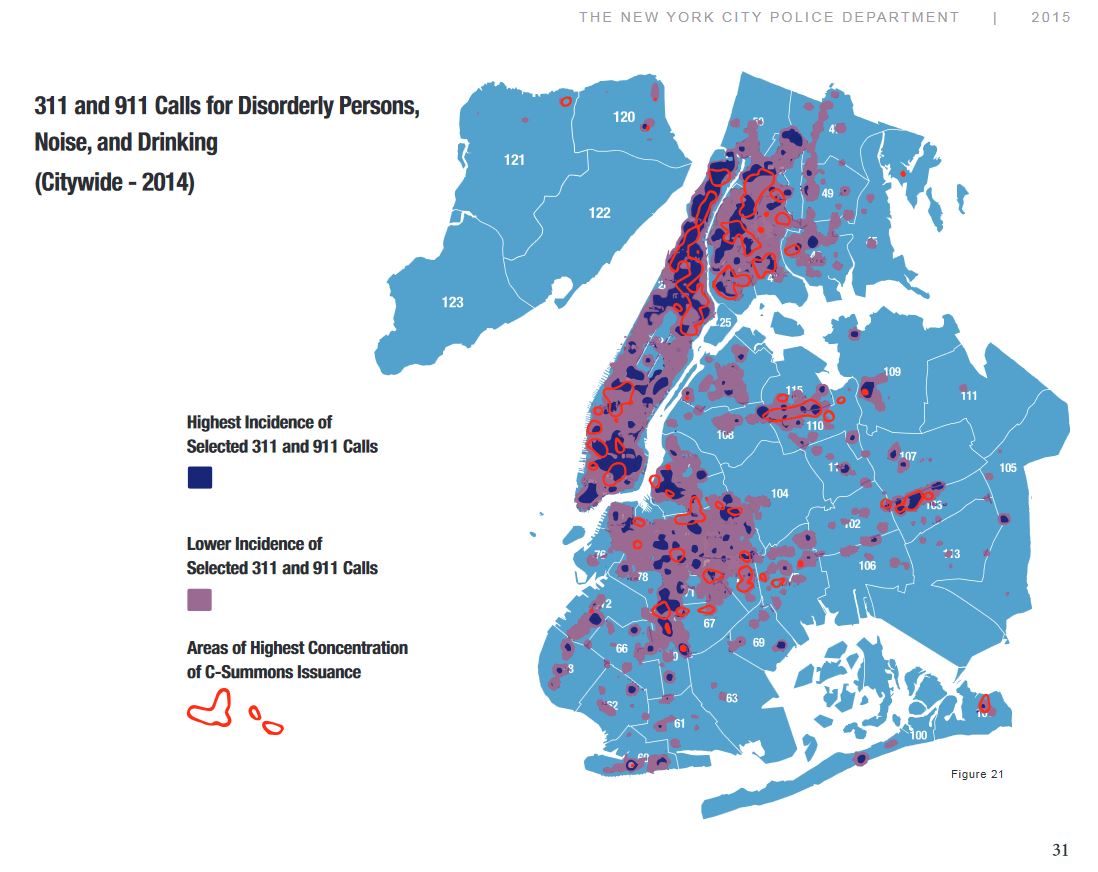

The OIG report largely ignores calls for service as a reason why quality-of-life enforcement may be pursued more intensively in one precinct than in another. As the NYPD has shown in its own report on quality-of-life policing “Broken Windows and Quality-of-Life Policing in New York City,” racial disparities in enforcement of minor laws in New York City can be largely explained by calls for service that have pulled officers to particular locations and particular offenders.

It’s worth pausing here. This is important. Quality-of-life enforcement — which does affect minorities disproportionately — is in response to minority citizens’ calls for service. Here’s a page from that linked-to report.

Quality of life enforcement happens because residents want it to happen. And residents in black and hispanic neighborhoods call police for quality-of-life issues most of all.

In the name of racially non-disproportionate policing, should police ignore these calls for service? Not according to the poll data of New York blacks and hispanics (page 21). Similarly there’s a 2015 Gallup poll that showed 38 percent of blacks (nationwide, compared to just 18 percent of whites) want more police presence; just 10 percent of blacks want less police presence. Blacks want more policing more than whites want more policing. You wouldn’t sense that from the current cops-are-the-problem. Now of course more policing and better policing are not mutually exclusive, but it comes down to this: you can’t have community policing if you ignore the quality-of-life issues the community cares about.

Comments

3 responses to “NYPD: “Broken Windows Is Not Broken””

The big question is whether Broken Windows policing reduces serious crime. The DOI tried to answer that question. I haven't read the report you are referring to, but from the excerpts here, I can't find any reference to evidence on that big question. It says that the DOI report was faulty in the way it defined and measured the variables. But does it provide evidence based on the correct definition and measurement? And does that evidence show that Broken Windows policing works?

I think Braga et al.'s meta-analysis is the best summary. And it's most affirmative.

But more importantly, I don't think that is the big question. I think quality-of-life policing stands alone as a positive, when it reflects a community's desire for order maintenance.

All that said, it would be nice if the NYPD got a bit more in the research game. Police tend to think it's not their problem: "We save lives, let those academics debate." But by being so hostile to outsiders (less so now, but certainly under Kelly), the NYPD has had to spend a lot of time defending tactics retroactively.

Sorry if this is a bit off topic but I'm wondering what the connection is between Broken Windows theory and stop and frisk policies? Are they the same thing? How do they differ?